But we can see from COP 26 and other PR events that waiting for governments to act on our behalf in a meaningful way is likely to be disappointing. None, if any, show the kind of leadership which considers the long-term national or international interest to be of more importance than short-term political factors.

So we are likely to need a collective effort by individuals. But if that is to have any effect at all, it needs to be practical action.

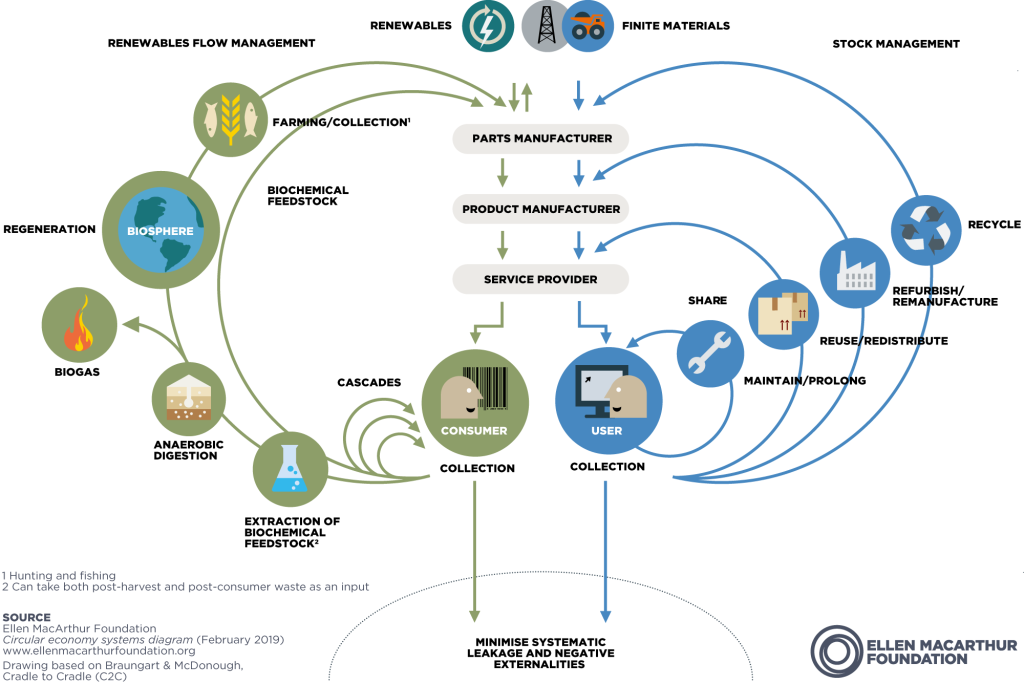

In brief the circularity argument means a shift from the linear make-use-dispose model (as at the moment, sometimes with fast fashion even ditching the use part of it) to a circular make – repair – recycle. The Ellen McArthur Foundation, a leading protagonist of the circular economy, points out in their recent report (2) that while emission control and decarbonising can go a good way towards achieving emissions targets, there is nearly as much to be had from reducing the emissions which come from the production of new things.

Naturally, this report operates at a pretty high policy level – even the “deep-dives” into mobility and the built environment don’t reach as far down as bottom-feeders like me.

At a more practical level an interesting idea was developed between 2012 and 2016 under the aegis of the Royal Society of Arts – “The Great Recovery” (3). Alongside a number of other design-related initiatives, this project looked at consumer durables from the perspective of design. In particular a number of workshops were held where items were dismantled by designers and assessed for repairability. This highlighted just how irreparable items had become, which is an issue I look at in the Repair Process and Repair Log sections of this site, and which has been taken up by “Right to Repair” campaigns. Incidentally it seems a real shame that the project came to a halt in 2016. I wonder if some of the workshop events could be re-visited; something I’ll look at in the Mend Shed section. In future, designers who design for a circular economy will undoubtedly be a good thing. But if we want to reduce the amount which goes to landfill, we still have the question of what we do with the stuff which exists today.

Now if you want to be really shocked, the “Waste Age” exhibition at London’s Design Museum is the place to go. It brings into clear focus a number of issues in terms of the amount of waste we produce, and what happens to it. A particularly striking aspect is the waste created in producing virgin materials. That makes it well worth recycling say 1 kg of copper; to make it new creates some 200 kg of slag. If you can’t get to London before the exhibition closes (it runs until 20th February 2022), then the companion publication (4) is well worth getting. It is compelling reading.

Though they do a good job at keeping big and important issues on the agenda, I’m not a fan of activists’ tactics (like XR and Insulate Britain). In my view they irritate more people than they persuade. And while it may feel good to bang a drum or person the barricades or demand the end of capitalism and so on, I’m not convinced it achieves a lot. Maybe that’s just me.

Clearly there are things we can all do to reduce emissions. We could for example eat less red meat, stop flying, walk or cycle more. As well as reducing our carbon footprint these are likely to have benefits to health. There are many lists available, for example here.

Another strand could be to pick up the threads of the circularity argument. To recall, it means a shift from the current linear model of make-use-dispose to make – repair – recycle. I’ll explore the implications of that in the Repair Process section.

In terms of individual behaviour it implies a new relationship with our things. It will be a shift from ownership of essentially disposable things to stewardship of longer lived items. That stewardship will involve being informed about what you are buying in the first place and either maintaining or organising the maintenance of the item through its life. Status would start to derive less from boxfresh/pristine, more from well-loved.

In time it may be that the industrial structure develops as well.

The next sections look at the practicalities of repair, initiatives related to it and some resources available.